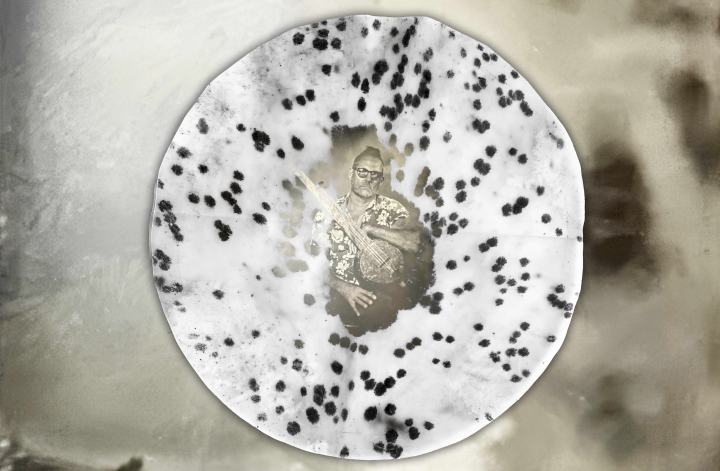

Country Rebels w/ Jeff Menzies

Jeff Menzies is a visual artist, musical instrument maker and educator, currently practicing and living out of Jamaica, Treasure Beach, St. Elizabeth. Jeff has been making musical instruments for 28 years now, specialising in and inspired by the history of the banjo.

Tell us about how you started building instruments Jeff.

Jeff MenziesI was doing undergraduate work in sculpture at the Ontario College of Art and Design in Toronto, Canada. I worked with various sculpture materials and processes and at that same time, I was also learning how to play old time music. Pursuing, practicing and researching musical instruments.

Later on, I started working with a banjo maker by the name of Wyatt Farley, and that really enabled me to hone my skill sets and deepen my understanding of luthiery practices (the art of making stringed instruments).

As soon as I did that, I realised that it was the same practice. As soon as that light switch went on, I couldn't separate musical instruments from art objects. Some of my faculty would resist the fact that musical instruments are art objects, and that's because of the word ‘function’. As soon as something has utilitarian references, it’s no longer seen as high art. But why can't high art visually function? Why isn't visuality a function?

So, you had a rebel moment there?

JMYeah, definitely a rebel moment. I don't draw parameters around creative practice, because it's all comprised of the same language of elements and principles. The music and the tunes that I was playing, were feeding my sculptural objects. I started to use gourds as an investigation within my visual practice, and at that time, I didn’t know about the gourd banjo.

It was a friend that directed me towards it years later. He sent me a gourd banjo, and as I pulled it out of the box, the strings vibrated on the packing material. I had that sonic experience, and I was sold on it instantly. It gave me clarity and perspective to this new journey that I'm on.

28 years later, it still feels new to me, because I'm still early in my days and exploring it.

So, what is it about the banjo specifically? And what’s the connection of the banjo to Jamaica?

JMA very early form of the banjo traveled from Africa, through the Caribbean, and up to the Americas through the slave trade. An instrument called the banza was formed.

When you have a plantation, with say a hundred slaves on it, chances are they were coming from various countries, they didn’t speak the same language, they had different religions, and were forced to live in a very treacherous, traumatic, small area.

Their musical traditions were extremely different from each other, so for them to unite as one, they have to find a compromise. And that compromise is what the banza is. Out of many, one people (the motto of Jamaica). The banza represents exactly that coming together.

The banjo, exists in Jamaica now mostly within mento music, the early 1900’s folk music, influenced by calypso, the Cuban music and African folklore. It's beautiful music, there aren't a lot of mento bands playing anymore. You know, Jamaica's all about pushing forward towards new sounds, so in that process, mento has kind of been left behind. But there are still a lot of people that are aware of the banjo In Jamaica, because when they were growing up, their dad or their grandfathers, grandmothers or uncles, where playing the banjo. It's exciting when locals come into my studio and as soon as they see the banjo, they instantly associate and connect with it.

I've been working with vessels from the beginning of my time. Looking at the human body as a vessel, a carrier for memories, ancestry and culture. That's exactly what the gourd does in the gourd banjo. It speaks very much about Africa, about the Caribbean, about travel, about hardship, about suffering, about containing oneself for preservation, for celebration.

The director of the Jamaican Music Museum, Herbie Miller is a good friend of mine and we are constantly in a state of conversation around this need to preserve. You need to know where you come from to be able to move forward, you know?

**I have a question exactly about that. Jamaica is very musically innovative; it sparked so many new movements. Sometimes it feels like it touches on a very big musical subject, and then it keeps moving on rapidly to the next thing. Different peoples around the world collect these pieces and it inspires them to develop it. UK music, reggaeton, dub of course.

Now, that’s kind of the opposite of what you just said about preservation, but do you think there’s a need to forget in order to innovate?**

JMA need to forget. That's a fascinating... Well, yes, I mean, when you come from a hard place, a dark place, that is saturated in trauma, yes, you want to forget and move forward. Jamaica comes from all of this. The Maroons, which are communities of slaves that rebelled against their slave masters and ran into the jungle, ran into the rural communities and fought them off and started their own communities. So absolutely, the need to forget is just as relevant in this as the need to preserve and it can take you so far, you know?

It's easy for me to say all of these things because I'm very sensitive to my privilege and where I come from. I've never seen a more creative, industrious, spiritual, funny, loving, warm group of people in my entire existence, traveling this world. Their talent is just inherent within them. But it moves quick. And then as you said, internationals, foreign people are instantly inspired by it and use it to create their own work from it.

It's crazy, how this land holds so much energy.

JMYou know, in 2018 I think it was, I started a PhD work in visual arts, and ended up leaving that program to come back to Jamaica. This is where my research needs to be, in the field, allowing the materials to inform me. Allowing the people to inform me. Allowing the nature and the smell of dirt to inform me. Smelling a gourd. The impact that has on my work and my research is far superior than any PhD could provide me with. So, I came back to Jamaica.

I've tried to leave several times, but I always come back. And now I put my hands up and I say, I'm here Jamaica. Let's do this. Let's work this out.

I’d like to hear from you more about community and its importance. Locally as well as international.

JMCommunity is everything. That is how I've been able to navigate the world. Community is a universal language. That is why I am excited to start the Jamaica Center for the Arts, because I can't do it on my own.

Some people would ask me, well, don't you get lonely In Jamaica? I say, no man, I'm surrounded by the entire world. I'm not just surrounded by my immediate community, I'm surrounded by my global community. That's partially due to the technology, yes. So again, it's back to the beginning of this conversation, I don't set parameters. As soon as you set a parameter, you isolate yourself. I don't live in Jamaica. I live in the world, I'm surrounded by my worldwide network.

So, tell us about the Jamaican Center for the Arts. What is it, what's the vision?

JMYeah man, the Jamaica Center for the Arts has been in the back of my mind since landing in Jamaica 15 years ago. The Jamaica Centre for the Arts will be an art and research facility where people can come and learn about the history of Jamaican music, instruments, visual art and folk practice. As well as have Jamaicans can learn from internationals that are coming with their experiences and have it like a melting pot. Because that's where things become their most beautiful, when things are melted down together, you know?

Again, I'm not going to draw any parameters to the type of educational offerings. I believe that if you separate painting, drawing, printmaking, photography, sculpture, dance, architecture and what it means to play music, you reduce the ability to understand the art.

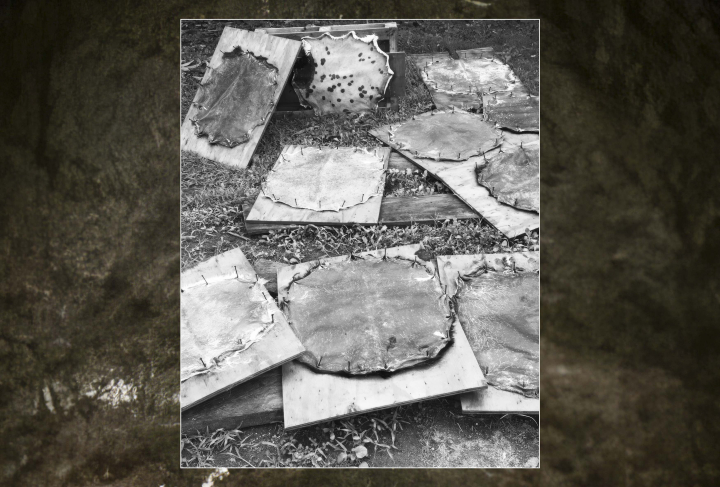

I actually just had my first class in the Jamaican Center for the arts recently. It was gourd banjo making workshop. Eight people flew in from all over the U.S. to join me, which was incredible. It was groundbreaking to see the level of support that I received and continue to receive on this project.

We were all making banjos in the context of Jamaica, and what a great opportunity to understand the lineage, history and roots of this instrument in than doing just that.

They got to hear the stories of the people, of the materials, they got to feel how hot the sun is as they were working. Teaching is a big part of my creative practice. A mentor of mine was saying, we're all on the same level, we're just at different points in the path. It's not about me projecting information towards them. It’s a circular effect just like the acoustic circuit on a musical instrument.

We are vessels and we exchange vibration.

Link up with The Jamaican Center for the arts to support the work and find more info about future programs.

Tune into the Country Rebels Chapter 6 to listen to more of the conversation and to the sounds of Menzies instruments.