Are you ‘Comfy’?

[This feature was written months prior to Bristol’s Black Lives Matter protest of 07/06/2020]

What’s your most ‘uncomfortable truth’? Maybe you were a bully at primary school tormenting the kid with funny walk in the playground. The thought of it may induce anxious sweating and heart palpitations, but, what if we applied the same way of thinking to museums? It should be easier as museums are inanimate, they can’t get anxious or overwhelmed. Museums are buildings, dedicated to human knowledge and history. Knowledge is power, correct? The power of hindsight can be argued to be one of the human race’s greatest strengths. No other being on planet earth can do this. Museums should be comfortable with their truths. Shouldn’t They?

So why have a cohort of students, from rival universities, made a project at Bristol Museum and called it ‘The Uncomfortable Truths’? They say the aim of the project is to ‘uncover uncomfortable truths behind museum objects — how they were collected, what they represent and the difficult pasts that are hidden behind them’. Stacey Olika’s the creative director for the ‘Uncomfortable truths’ project. Scrolling through her Instagram my eyes are drawn towards the word ‘visionary’ in her bio. When asked what the idea behind the project is, she says: ‘We want to start a conversation, about decolonisation, and starting for us to think about accountability and ownership. To not give people one-sided views of how these artefacts were acquired’. True to her self-titled visionary status ‘The Uncomfortable Truths’ project is the only one of its kind in the city. She emphasises the great importance in the truth being ‘uncomfortable because, comfort breeds ignorance, and ignorance doesn’t allow us to move forward’.

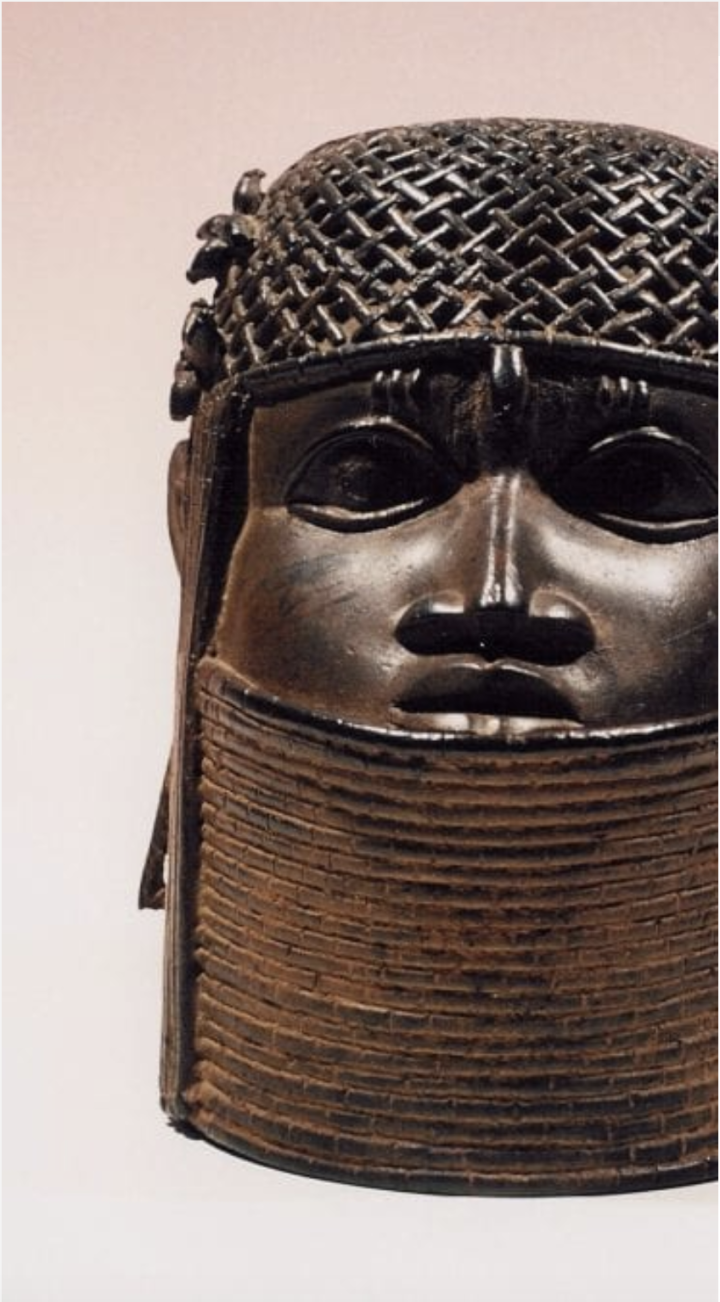

The project analyses artefacts like the Benin Bronze heads; Benin was a Kingdom (not country) in a southern Nigeria, before Nigeria was colonized by Great Britain. A kingdom burnt down by the Great British Empire in 1897. The project’s podcast explains how the heads ‘Focus attention on the violent and painful stories of colonial rule in Africa’. Furthermore, ‘The reason these heads are no longer in Africa is because they were taken — forcibly — in Benin’. The aim is to not only bring light to these uncomfortable truths in museums, but also start a wider conversation around topics such as ‘How would returning the heads be a positive move to undo the injustices of the past?’. Furthermore, ask ‘How do you approach the conversation around white guilt in regard to colonialism?’ The solution points towards exhibitions like this. Olika feels that for those who curated the exhibit ‘had their voices heard for the first time in long a time’.

The painting of ‘The Battle of the Saints’ has closer links to the city. This painting celebrates, the British military victory over the French invasion of their Caribbean islands. The podcast explains that the painting can be seen as Britain taking pride in the ‘nation’s ability to protect their slave islands and continue to exploit persons racialised as Black’. Visitors to the museum, simply aren’t given this information. Olika explains the project forces people to ‘question themselves a lot, in order to start a conversation.’ People don’t realise the importance of the Caribbean islands to the British empire, and how slavery among many other goods was exceptionally profitable at the time. The ability to empower young people through knowledge is vital, ‘For people like us, it shows that young people are putting representation into the light’. Museums can be seen as the first step in the right direction, to ensuring false narratives aren’t glorified.

Finally, the last ‘uncomfortable truth’, the building itself. The ‘Wills Memorial Building’, This neo-gothic landmark sits proudly at the top of Park Street. Home to not just the Bristol Museum, but also the Law faculty of Bristol University. Jon Worgan is a 23-year-old musician who was born and bred in Bristol. When asked what he knows about the building's links to slave-trading history. He admits that he ‘doesn’t know enough’, so he finds it hard to form a coherent opinion on name changes. He’s definitely not against the idea once he’s given the correct information. Not every Bristolian knows the city’s history, but how can one learn if the information isn’t easily accessible? For Olika, people like John have wrongfully become victims of these false narratives.

The Wills family were prominent tobacconists in Bristol. The Wills family owned, WD & HO Wills which became part of Imperial Tobacco in 1902. At the peak of The Wills’ tobacco factory in 1912 it employed 40% of the working population of Bedminster, Ashton and Southville. The family even donated money to the campaign for the abolition of slavery in Bristol. Nevertheless, the Wills family were aware that their tobacco, was coming from Slave labour in the Caribbean. Does this excuse them from profiting from slave labour?

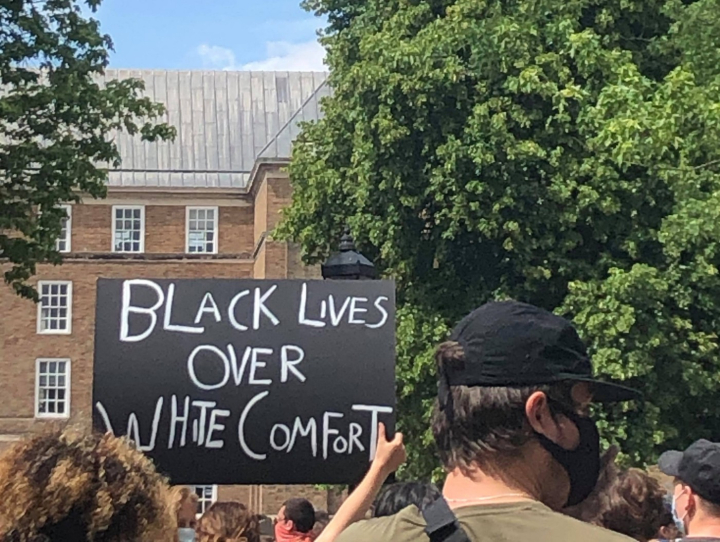

The uncomfortable truths of Bristol don’t stop within the ‘The Wills Memorial’. Just a few minutes’ drive down Park Street, past College Green the historical centre of protest, you arrive in the recently finished town centre to find the statue of Edward Colston. The plaque reads this ‘A memorial of one of the most virtuous, and wise sons of the city’. Colston was a trader in cloth, wine and sugar; and let’s not forget he was also a Slave trader, a very important slave trader. In 1680, he became an official of the Royal African Company. The Royal African Company had the sole charter to buy and sell goods in Africa according to the British empire. One of their many goods he exported between 1672 and 1689 were 80,000 slaves men, women and children. With all this information at hand the question comes to mind; How does this left-wing, hipster paradise deal with its uncomfortable truths?

Surely in a left-wing city, where the guardians of political correctness rule with an iron fist. In a society where social platforms have morphed into the public sphere, a Wild West where the sheriff badge says ‘#woketwitter’, how are such names still glorified? Bristol has several monuments named after Colston. Let’s make it clear all this information isn’t new, The band Massive Attack refused to play at Colston Hall! One of Bristol’s biggest bands refused to accept these uncomfortable truths. In protest of false narratives. The students who curated the exhibition are paying direct homage not just to Massive Attack, but also their forgotten ancestors.

If we remove Colston & Wills from the city, completely eradicate them; What will the city lose? Councillor Richard Eddy is the conservative councillor of Bishopsworth, in the southwest suburbs of the city. He’s been a councillor for more than 20 years; and considers himself a ‘true’ Bristolian. He has even traced back his family history to the Reformation in the 16th Century. His view is that ‘If it’s going to be authentic, it needs to reflect both sides’. What he doesn’t want to see is the suggestion that ‘everything before 1945 was uniformly bad’. He believes in focusing less energy on the past and putting more time into present issues such as ‘modern slavery’. Yet he fails to mention any campaigns he’s involved with. ‘The slave trade was wrong; we can say that with hindsight. But it was lawful at the time’. He feels Colston and Wills are remembered for using their wealth charitably, which in turn has benefited generations of Bristolians, ‘We should honour people who have shared their fortune’.

Councillor Richard Eddy voiced the concerns of his constituents when they say that ‘this is no longer their city, all their history is being slowly thrown out’. But he strongly urges people to remember ‘Right or wrong this is the History of Bristol!’. Since the start of campaigns to rid Bristol of the Colston and Wills names, only one institution has officially changed its name. A primary school in Cotham; ‘I personally believe there is left-wing political agenda, which has permeated throughout the education system. What the governors did about Colston Primary School, was an abject example of appeasement…To the left-wing politically correct agenda, which is seeking to destroy any pride in Great Britain.’ Eddy firmly believes Britain is ‘Great’ because ‘When you compare us to many other countries far and more treasure and blood was spilt to reach 100% democracy’.

Dr Madge Dresser is a former history professor from The University West of England, Bristol. Her extensive knowledge of Bristol’s past allows for an informative yet extensive conversation. Her Jewish upbringing allows for a different approach of thought ‘Why did some Germans love the Nazis so much? What was in it for them? You have to understand the attraction of certain world views…It’s important that you understand why they felt it was rational to feel the way they do’. Dr Dresser believes to deal with our ‘uncomfortable truths’ we must understand another person’s malice, this isn’t easy, it takes time and the ability to separate yourself from your own feelings. Only when that malice is fully understood, can you begin to find a solution. Prof. Dresser believes Bristolians aren’t given a ‘proper’ education about their city’s history. They simply don’t understand that ‘The object of the goal was to make Britain great not Africa.’ Are they the ones to blame?

Students in the UK seem to spend more time learning about the American civil rights movement than their own. Yes, the actions of the American civil rights movement did inspire people of Colour in the UK. But why do we not learn about the people who were inspired? Bristol played a significant role in the civil rights movement here in the UK. How much do you know about Paul Stephenson, Roy Hackett, Owen Henry, Audley Evans and Prince Brown the organisers of ‘The Bristol Bus Boycott of 1963’. The men who formed the West Indian Development Council that led and organised a boycott of the Bristol buses, by the West Indian community, successfully led to the lift of the colour bar. Allowing for Black and Asian workers to be employed at the Bristol Omnibus Company, coincidently falling on the same day Martin Luther King gave his “I Have a Dream ‘speech in Washington on the 28th of August 1963. The Boycott was such an influential event it even aided the passing of Race Relations Act of 1965 which made “racial discrimination unlawful in public places” illegal. So why isn’t our education choosing as narrative much closer to home?

For Prof. Dresser the solution to Bristol’s uncomfortable truths may be this ‘We need to extend the idea of critical thinking, to encompass all our experiences. Such as our emotional thinking, so that we don’t romanticise. “Oh well it was great; all the African kingdoms were wonderful and the British were all evil”, I don’t think that’s capturing the truth either.’ According to Prof. Dresser sharing this information isn’t enough, what’s vital is for people to engage with it. ‘People have to think! People in the public arena often want a simple answer. They want goodies and baddies.’

Our political system is based around the chosen few, reflecting the views of the many. When those chosen few, directly or indirectly enforce false narratives it becomes the job of the many to inform the many. To start well-informed discussions, which include everyone in the hopes of finding the correct answer to our ‘uncomfortable truths’. Bristol will never escape its history, but in this new age of political correctness, can we go too far? Will we whitewash Bristol’s history? Even Olika isn’t sure. In her uncertainty, there is a fear as she describes of people coming for her ‘neck’. ‘I’m still in a little back and forth on the name change.’ Changing the name of monuments will never fully right the wrongs of the British Empire. The truth is, says Olika ‘The effects still remain today. I’m not walking on a completely peaceful earth, where I can walk the streets and not be judged, or say “Racism doesn’t exist!” We are still facing the effects of what happened, of what was lawful during those times.’ Nevertheless Olika ‘doesn’t see why it would be a problem if we changed the names…Let’s talk about why! let’s have this whole conversation as to why! Let’s bring in a huge focus group, a huge variety of people and talk about why this name should be changed. And tell us, if the process of the name changing is difficult. Then tell the public what the difficulty behind it is!’. Maybe the best way to deal with Bristol’s ‘uncomfortable truths’, is simply to start talking about them.

My experience with Colston :

I walked countless times over 4 years without knowing I was walking past the oppressor of my people. The lack of education on the atrocities of the British empire essentially has made us blind. The resurgence of BLM movement across the world has led to us the people beginning to properly take off their blindfolds. The most effective way to do this is with an education system that doesn't hide the ‘truth’, it is only because of knowledge the ‘virtuous, and wise sons of the city’ no longer watch over the city centre. The many have done what they deem necessary because the chosen few wouldn’t. The people of Bristol haven’t erased History, they have made their own. This movement is for change now, not “in a bit”. To achieve real change The death of George Floyd must be the straw that broke the camel’s back.